“Gain of function” (GoF) research refers to genetic modification that deliberately enhances the abilities of an organism — often a virus or bacterium — to study how such changes affect its function, transmissibility, or virulence. In simple terms, it means imparting a new or stronger function that the organism didn’t previously have. Such modifications, which have been performed for decades, have been extraordinarily important, from inducing bacteria to synthesize pharmaceuticals to imparting pest-resistance to crop plants.

Despite the importance of GoF modifications, they have sometimes faced misplaced concerns or opposition that could lead to their being overregulated or even banned.

What Is Gain-of-Function Research?

In the simplest terms, “gain of function” is a broad category of research that involves genetically altering an organism to give it new abilities or characteristics. In biomedical or other sciences, GoF studies have many purposes:

- Understand disease mechanisms — for example, modifying a virus to see how specific mutations affect its ability to infect cells or evade the immune system. For example, GoF experiments have been crucial for increasing our understanding of bacteria like Mycobacterium tuberculosis (which causes TB) in the pursuit of discovering new treatments.

- Develop treatments — by altering the microorganism to synthesize a pharmaceutical. GoF-modified E. coli synthesize human insulin, and modified baker’s yeast (Saccharomyces cerevisiae) produces the antigen in Hepatitis B vaccine. GoF research has also been used to create CAR T-cells for cancer, and modified adenoviruses used in gene therapies for muscular dystrophy.

- Other uses – GoF techniques have also been used to improve crop resiliency and animal health and other characteristics. An example of the latter was the addition of a Chinook salmon growth hormone gene to the Atlantic salmon to create a version of the fish – the AquAdvantage salmon — that grows to maturity in about half the time of the unmodified fish.

- Model potential pandemics — by studying how animal viruses might mutate and adapt to infect humans.

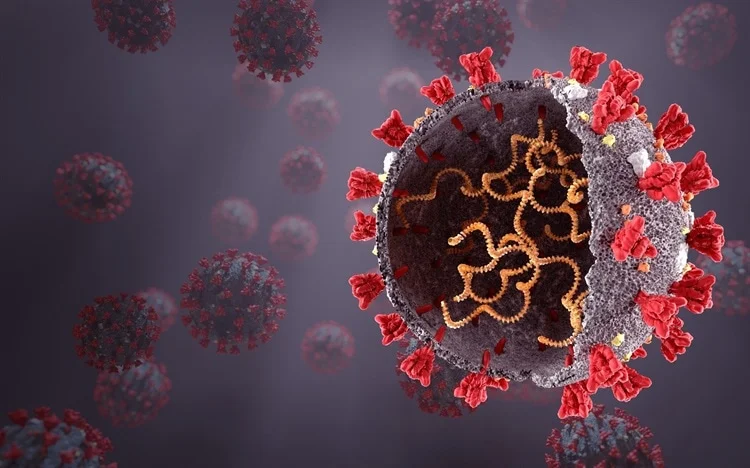

Many such studies are completely benign — like most of those mentioned above or tweaking yeast or fruit-fly genes to study metabolism. Controversy arises with the modification of potential pandemic pathogens (PPPs), highly transmissible and/or virulent agents that could cause widespread illness if released accidentally.

Why It’s Controversial

1. Risk of Laboratory Escape

Critics worry that enhancing the pathogenicity or transmissibility of viruses — such as influenza, SARS, or other coronaviruses — creates the possibility of spread of a dangerous infectious agent if there is accidental release from the lab. The fear is that, depending on the enhanced or new function of the organism, a laboratory accident could spark an outbreak similar to naturally occurring ones.

This concern intensified after reports of safety breaches at U.S. labs (e.g., anthrax, influenza, and smallpox incidents at U.S. government labs in 2014) and debates about coronavirus research performed at the Wuhan Institute of Virology in Wuhan, China.

2. The Dual-Use Dilemma

GoF research is “dual use” – that is, it can advance science and medicine but also provide a roadmap for bioweapon development. The same mutations that help scientists anticipate viral evolution could, in the wrong hands, be exploited maliciously.

3. Ethical and Oversight Concerns

The question is not whether such research can be done but whether it should be done — and under what conditions. In 2014, the U.S. government imposed a moratorium on federally funded GoF research involving influenza, SARS, and MERS viruses. This pause was lifted in 2017, replaced by a stricter oversight system known as the Potential Pandemic Pathogen Care and Oversight (P3CO) framework. Critics argue that oversight remains opaque and inconsistent.

4. Scientific Divisions

Some virologists insist GoF experiments are indispensable for understanding how viruses mutate and for designing better vaccines and antiviral drugs. Others argue that computational models, pseudovirus systems, and field surveillance offer safer alternatives without creating potential new hazards.

The Broader Debate

The GoF controversy is as much philosophical as technical. It pits scientific freedom and preparedness against precaution and biosecurity. The key questions include:

How much risk is there in GoF research?

How much risk is society willing to tolerate in pursuit of knowledge that might avert future pandemics?

- Who decides which experiments cross the line?

- How can oversight keep pace with biotechnology’s accelerating power?

- Should the knowledge that U.S. adversaries are working on bioweapons influence domestic policy?

Lack of Common Sense

When I was a Special Assistant to Dr. Frank Young, the Commissioner of the FDA, he used to counsel his minions that regulation needed to be tempered by common sense – which has been wanting in the GoF debates.

An example is NIH’s order to University of California, Berkely Professor Sarah Stanley to halt her research on Mycobacterium tuberculosis, the bacterium that causes tuberculosis, because the work was deemed “too dangerous.” What was the rationale? The work often uses resistance to kanamycin, an antibiotic not used to treat humans because of severe side effects, in order to isolate mutated strains. The kanamycin kills all the bacteria except for those that are resistant. Thus, kanamycin resistance serves as a molecular marker that identifies and allows the isolation of the small percentage of mutants in a population that have been successfully modified, since only these bacteria survive when exposed to the kanamycin. That is the bacteria’s “new function.”

In any case, all the kanamycin-resistant strains are killed by clinically used antibiotics and cannot spread drug resistance to other strains, so they pose no incremental risk to the public. For decades, the selection of kanamycin-resistant mutants has not been considered dangerous by any reasonable definition. And yet, because kanamycin resistance is the acquisition, or gain, of a new function, it was (mistakenly) deemed to be dangerous by NIH. This is just one of many examples of the paucity of “gold standard” science currently at HHS agencies such as NIH, FDA, and CDC.

In Summary

“Gain of function” research is important in several ways. It can induce organisms to synthesize high-value pharmaceuticals or acquire other useful characteristics or to anticipate nature’s next move by creating them in the lab — but critics warn it could unleash what it seeks to prevent. The ongoing debate reflects a broader tension in modern science between balancing innovation with the imperative to protect the public from rare but catastrophic risks.

However, that balance must be governed by common sense. Precautions on genuinely dangerous GoF and other research – for example, on the influenza virus that caused the 1918-1920 Spanish Flu pandemic – are important. But effective, science-based oversight must distinguish between low-risk and actual, demonstrable threats so that we do not impede progress against deadly diseases for no real safety benefit. As Berkely Professor Sarah Stanley, whose tuberculosis research was halted, put it:

An overly broad approach, with the resulting ramifications for lifesaving research we’re already seeing, could be exacerbated by the recently proposed “Risky Research Review Act.” Without clear definitions, scientific expertise, and streamlined review processes, lifesaving research could be stopped. This would be an even bigger threat to public health than the broad, misinformed definition of “dangerous” that is being applied here.

Given the deficiencies of leadership in federal science agencies and the ignorance of scientific nuance that often emanates from Congress, it is difficult to be optimistic about the outcome for the foreseeable future.